PLASTIC POLLUTION IN THE SEA: CAUSES, CONSEQUENCES AND SOLUTIONS

Seas and oceans are vital lungs of our planet, regulate the climate, and are cradles of biodiversity. Plastic, used everywhere because of its versatility, does not biodegrade easily, and its excessive accumulation in the seas and oceans is compromising their function and has become a major problem.

Associations, research organisations and governments are looking for the best ways to curb and reduce this problem. The oceans cover three-quarters of the Earth's surface, contain 97% of the water on the planet, and represent 99% of the space, in terms of volume, occupied on the planet by living organisms (containing approximately 200,000 identified species): they are critical for life and climate regulation.

They are the Earth's thermostat: the first three metres of ocean contain the same amount of heat as the entire atmosphere; because of ocean currents, northern European countries have fairly mild temperatures. They are also able to absorb about 30% of all the CO2 emitted worldwide each year by human activities.

In 2018, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) listed the problem of plastic in the oceans as one of the six most serious environmental emergencies to be addressed.

The importance of the oceans is such that their protection has been included among the Agenda 2030 goals by the United Nations:

Goal 14: Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development, and specifically among the goals;

Goal 14.1: By 2025, prevent and significantly reduce marine pollution of all kinds, in particular from land-based activities, including marine debris and nutrient pollution. We must rebuild humanity's relationship with the ocean and place it firmly at the centre of future sustainable development solutions.

Why plastic in the seas and oceans is a problem

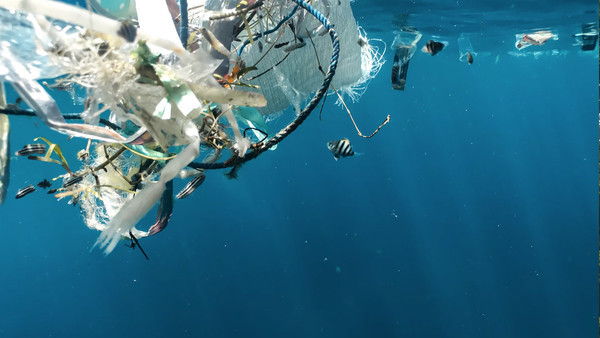

Plastics in bodies of water can occur in the form of macro fragments or objects (large parts of objects, bottles, caps, nets, pieces of polystyrene, etc.) or microplastics i.e. fragments less than 5 mm in size.

The problem of plastic dispersed in the seas and oceans relates to:

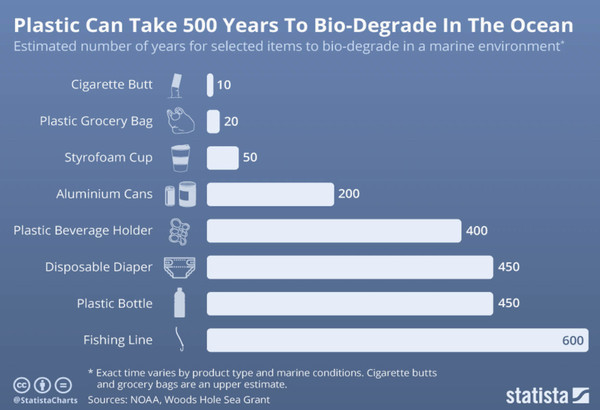

- the time it takes to degrade in the environment (even over 600 years);

- its fragmentation into small parts of plastic objects, becoming microplastics (less than 5 mm in size), which spread easily, attracting and absorbing pollutants dispersed in the oceans (e.g., pesticides, fertilizers, pollutants from industrial discharges, detergents and cosmetics);

- the possibility of even fatally injuring aquatic animals (fish, mammals, birds) that get caught in fishing nets, for example;

- its insertion in the food chain: fish, amphibians, seabirds and mammals can swallow chunks of plastic, mistaking them for food or they can be ingested in the form of microplastics; this can lead to problems in the intestinal tract, cause malnutrition and occlusion of the stomach and airways; the chemicals absorbed from plastic also enter the body's tissues and then act at hormonal level and beyond;

- it can become a trap for marine wildlife: birds or fish that get caught in abandoned fishing nets die of suffocation or because they cannot feed;

- it can be a costly and dangerous problem for shipping, as it can be a hazard and get caught in propellers and rudders.

Studies are focused in particular on microplastics that result from the mechanical fragmentation of larger plastic objects, cosmetics, various products for processing other materials, leaks from industrial plants etc. These fragments can easily enter the food chain of marine aquatic fauna, with both toxic and mechanical effects, leading to problems including reduced food intake, suffocation, behavioural changes and genetic alteration.

Microplastics are a global problem and also affect us humans. They reach us both through the food chain and by inhalation, ingestion from water and absorption through the skin. Microplastics have been found in various human organs and even in the placentas of newborn babies.

Waste that is difficult to dispose of

According to UNEP data, approximately 36% of all plastic produced is used in packaging, including single-use plastic products for food and beverage containers, of which about 85% ends up in landfill or as unregulated waste.

Of the 7 billion tonnes of plastic waste generated globally to date, less than 10% has been recycled. This means millions of tonnes of plastic waste is lost in the environment or shipped thousands of kilometres to destinations where it is mostly burned or dumped. The annual loss in the value of plastic packaging waste during sorting and processing alone is estimated at USD 80-120 billion.

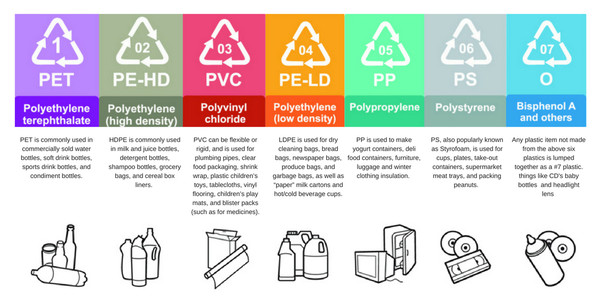

There is not just one type of plastic but a huge number of polymers with different characteristics depending on the uses they are intended for, and they require different methods of recycling. Polystyrene, high-density polystyrene, polyethylene and polypropylene are just a few examples of polymer types. The same technical characteristics that make plastics versatile and useful in any sector are therefore precisely those that make them difficult to dispose of.

How does plastic end up in our seas and oceans?

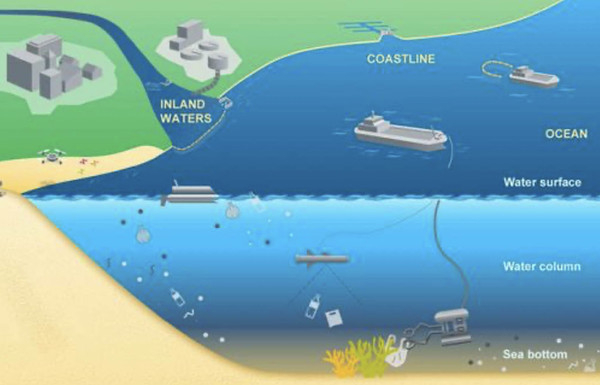

According to UNEP data, the main sources of plastics in the seas and oceans are:

- disposal of waste into the environment (littering), particularly near beaches and waterways;

- waste that weather events (rain, wind, snow) carry into waterways;

- fishing;

- transport;

- industrial activities, particularly in industries with processes involving plastic materials and improper waste management;

- agricultural activities that disperse often fragmented waste (tarpaulins, sacks, nets etc.) into the environment, which then reaches the sea through rivers;

- waste containers not properly covered and waste containment structures not tightly closed;

- inadequate treatment of wastewater and wastewater spills;

- illegal domestic and industrial waste dumps and poorly managed legal dumps.

UNEP estimates that 1,000 rivers are responsible for nearly 80% of annual global discharges of river plastics into the ocean, ranging from 0.8 to 2.7 million tonnes per year, with small urban rivers among the most polluting.

Plastic in the oceans: current data

According to UNEP data released at the latest ocean conference held in July 2022:

- marine pollution accounts for at least 85% of marine litter, and plastic waste is the main pollutant;

- 80% of the plastic that finds its way into the ocean comes from land sources;

- at least 11 million tonnes of plastic are discarded in our seas every year;

- every minute, a truckload of plastic waste is dumped into our ocean;

- it is predicted that, by 2040, the equivalent of 50 kg of plastic per metre of coastline worldwide will flow into the ocean every year.

Plastic islands and whirlpools in the oceans

Over time, marine currents have created areas where the concentration of waste is particularly high, and these areas are known as Plastic Soups. Worldwide, there are six particular whirlpools (gyres) of plastic concentration, which are found in the subtropics, above and below the equator. In these areas, there is no visible floating mass of plastic waste but only a higher concentration, mostly of microplastics, than in other areas of the ocean.

Other critical areas are called hotspots or plastic islands where the concentration of plastic soup is even higher than in the whirlpools. In this case, the concentration is not so much due to currents, but to the presence of polluting sources (e.g. urban areas, estuaries). There are plastic islands in the Mediterranean, and recently, an Italian island was discovered in the area between Elba, Corsica and Capraia, within the Cetacean Sanctuary.

The world's best known plastic whirlpools are:

1. the Arctic Garbage Patch;

2. the Indian Ocean Garbage Patch;

3. the South Atlantic Garbage Patch;

4. the North Atlantic Garbage Patch;

5. the South Pacific Garbage Patch;

6. the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

How could plastic be eliminated from the oceans?

Marine pollution is a complex problem; there is no one-size-fits-all solution, but we can all do something. Governments, businesses and individuals are getting involved through various local and international campaigns. It is important to address plastic pollution with measures on the entire life cycle of plastics, from design to disposal through production, use and recycling, addressing the sources of waste both on land and at sea.

Reducing plastic waste in the sea can be done through two channels:

- preventive measures, i.e. policies and actions that limit waste generation and consequently prevent it from being mismanaged and dispersed into the environment. These actions concern both us citizens and policies on waste prevention and management globally;

- physical removal through machines that collect plastic, barriers in rivers, and collection campaigns involving both fishermen and voluntary associations.

Preventive measures

Preventive measures, i.e. actions that avoid producing the plastic waste, may include:

- replacing plastic packaging with packaging of less polluting materials; reducing the thickness of the packaging itself; designing packaging with parts that are not easily lost in the environment;

- conscious design that reduces waste when processing goods, reduces thickness, uses types of plastics that are easily recyclable, and ensures that goods/packaging are designed in a manner that prevents plastic parts from being easily dispersed into the environment;

- reuse of plastic packaging, e.g. using it for loose products;

- using cloth or reusable bags for carrying items and groceries;

- avoiding the use of disposable products made of plastic materials;

- recycling all plastic packaging and items;

- not producing any i.e. not using plastic but other durable materials (e.g. glass, steel);

- reusing containers and packaging as much as possible either by buying products loose or by using end-of-life packaging for creative or other activities;

- avoiding the use of products (e.g. cosmetics) containing microplastics;

- recycling properly;

- raising awareness, educating those around us about the problem.

Thus, all policies and regulations aimed at waste reduction, prevention and recycling and the various national and international campaigns to raise awareness of the issue fall under marine litter prevention practices.

Physical removal actions

Removal of plastic waste can be done by:

- collection campaigns that call on citizen volunteers;

- beach cleaning by mechanical systems by beach establishments or local governments;

- using mechanical tools such as boats or barriers specifically designed to collect or block waste.

Examples of mechanical systems that remove plastic waste from the sea and ocean

In recent years, various systems have been invented to capture and initiate recycling of plastic dispersed in the oceans, seas and rivers. Some examples of systems in operation or being developed are provided below.

Dutch NGO Ocean Cleanup has designed and is testing the Ocean Array Cleanup System 001/B that can collect plastic debris of all types and sizes, from microplastics to ghost nets. It is an autonomous system that uses the ocean’s natural forces to passively capture and concentrate plastic. The system is very simple and consists of a chain of floating barriers, 2 km in length, which use the current, without nets, to channel plastic to platforms that act as funnels. Once a month or so, a boat collects the waste channelled to the central part of the system. This mechanism was created specifically with the goal of cleaning up the Pacific Trash Vortex and then going on to the other accumulation points in the oceans.

However, the NGO has not stopped at the sea but is also experimenting with river cleaning technologies such as:

- Interceptor Original river cleaning technology. River waste travelling with the current is guided by the barrier to the Interceptor opening;

- Interceptor Barrier that consists of an independent floating barrier anchored in a U-shape around the mouth of a small river, intercepting rubbish and buffering it until it is removed from the water.

The SeaCleaners team designed the Manta, a boat still under construction that is shaped like a huge catamaran. It is designed to collect, process and reuse large volumes of floating plastic debris found in highly polluted waters along coastlines, in estuaries and at the mouths of large rivers.

The SeaCleaners team is also behind The MAPP project (Mobula against Plastic Pollution). The Mobula 8 is a boat designed as an autonomous station for waste recovery and cleaning polluted areas. It is capable of collecting both floating macro-waste for pollution control purposes and micro-waste for scientific purposes, as well as hydrocarbons. It is particularly suitable for clean-up operations in calm and protected waters - port areas, lake areas, mangroves, rivers, canals and at sea up to 5 miles from the coast.

The Ocean Cleanup Array is the brainchild of Dutchman Boyan Slat. The first prototype will be placed off the island of Tsushima, located between Japan and South Korea.The ultimate goal of the project is to clean up the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. It consists of a system of floating booms, arranged at an angle along the path of the currents and anchored to the seabed, which funnel plastic towards collection points. Within them, there are special solar-powered crushers, which compact and prepare it for recycling without disturbing the routes of fish or the life of other organisms. The idea is to place within five years barriers along approximately 100 km that should be able to capture nearly half of the island's plastic trash. According to estimates, the Great Pacific Garbage Patch could be completely cleaned up in about 10 years.

Italian Projects

Lifegate has created the PlasticLess campaign, a project based on three main actions:

- communication to inform people about the risks of plastic in the sea;

- promotion and dissemination of good sustainable practices;

- concrete actions to remove trash floating in our seas thanks to Seabin, bins placed directly in the sea at ports and marinas capable of removing up to 500 kg of plastic waste per year.

Poralu Marine, a world leader in facilities, products and services for port operations and a lead partner of LifeGate PlasticLess, has released a new range of devices called “The Searial Cleaners” to remove plastic from the seas:

- Trash Collec'Thor is installed on floating docks in harbours and marinas, near accumulation points. It can capture different types of floating waste including plastic bottles, bags, butts, etc., and collect hydrocarbons and microplastics from 3 mm in diameter and over. Experiments have shown how the device can capture up to 100 kg of floating waste at a time. Finally, emptying and cleaning are made possible by a handy winch that helps lift the bin;

- Pixie Drone is a small underwater robot just over 1.60 m long, 1.15 m wide and just over 50 cm tall – the drone works in a water depth of at least 30 cm. It can be remote-controlled from a distance of 500 metres and monitored through a web app. It has a speed of 3 km/h and an operating range of six hours. In each of its missions, it can collect up to 60 kg of waste at a time: plastic, organic waste, glass, paper, textiles, rubber and hydrocarbons. Its work is also aided by a camera with a range of 300 metres;

- Seabin is a waste collection bin floating in surface water capable of capturing around 1.5 kg of debris per day (equivalent to approx. 500 kg of waste per year) including microplastics from 5 to 2 mm in diameter and microfibres from 0.3 mm. The device is submerged in water with the top of the device at surface level. Through a pump connected to a power supply, it can treat 25,000 litres of water per hour. The waste is captured inside the basket, which can hold up to a maximum of 20 kg, while the water flows through the pump and back into the sea.

Ogyre, an Italian social impact start-up, is the first online platform seeking to manage and coordinate the recovery of waste from the sea by fishing communities.

Fishermen collect plastic that gets stuck in nets and take it to ports where partners report it and send it for recycling. Ogyre bears the cost of recovering and disposing of the waste and allows the fishermen to go about their normal fishing activities and receive additional payments for recovering the plastics from the sea. Fishing for Litter has the advantage that it does not require specific vehicles or technology to be rolled out: it catches the plastic directly through the fishermen's nets, the same nets used to catch the fish. Ogyre funds itself through the sale of costumes and clothing with the association's logo.

The Institute for the Study of Anthropogenic Impacts and Sustainability in the Marine Environment (IAS) of the National Research Council in Genoa, Italy, took part in an international study that assessed and analysed all existing innovative solutions to tackle plastic pollution in the oceans. The study, Global assessment of innovative solutions to tackle marine litter, was published in Nature Sustainability and analyses most existing innovative solutions, technologies and methods to prevent, monitor and remove marine litter. Drones, robots, conveyor belts, nets, pumps or filters are used in the technologies, depending on the area of application: coastal areas, sea surface or ocean floor. Up to now, many systems have been based on technological approaches, but in the future it will be important to use integrated solutions, based on artificial intelligence, robotics and automation. The study highlights how the scientific community has focused its research mainly on monitoring marine litter, while NGOs act more on prevention: the synergy between various promoters, on the other hand, focuses mainly on removal techniques. The study also addresses the limitations of existing solutions by providing some recommendations for future programmes and financing tools.

Policies and campaigns against plastic pollution in the sea

Governments and various associations have for years been promoting standards, programmes and campaigns focused on the prevention of marine litter and its collection. Some examples of the best known are provided below.

International Maritime Organization (IMO) strategy to address marine plastic waste from ships:

In 2021, the IMO's Marine Environment Protection Committee (MEPC) adopted a strategy to address marine plastic waste from ships. The specific measures proposed are:

- studying marine plastic waste from ships;

- examining the availability and adequacy of port reception facilities;

- proposal to make the marking of fishing gear mandatory, in cooperation with the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO);

- promoting the reporting of lost fishing gear;

- facilitating the delivery of recovered fishing gear to coastal facilities;

- reviewing provisions for training of fishing vessel crew and familiarisation of seafarers to ensure awareness of the impact of marine plastic waste;

- considering the establishment of a mandatory mechanism to report the loss of containers at sea and identify the number of losses

- raising public awareness;

- strengthening international cooperation, particularly the FAO and UN Environment.

The strategy set out to achieve additional goals, including:

- increased public awareness, education and training of seafarers; better understanding of ships' contribution to marine plastic waste;

- better understanding of the regulatory framework associated with marine plastic waste from ships.

In March this year, a landmark resolution was adopted by countries at the fifth session of the United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA-5.2), which called for an intergovernmental negotiating committee to be convened to develop a legally binding international instrument on plastic pollution, including in the marine environment, by the end of 2024.

European regulations

Directive 2008/56/EC – European Action in the Field of Marine Environment Policy and its subsequent amendment by Directive 2017/845 sets out the European Union Marine Strategy. The Directive defines the Union's common approach and objectives for the protection and conservation of the marine environment in view of the pressures and impacts of harmful human activities, while allowing for its sustainable use, through an ecosystem approach. In summary:

- it provides for the implementation of research and monitoring of marine systems to assess the state of the marine environment and the impact of human activities;

- it contains a definition of ecological status based on a list of 11 descriptors;

- it provides for the establishment of a network of marine protected areas;

- it calls on governments to set up programmes of measures to achieve a good environmental status;

The directive is currently under review.

The European Union has also issued a directive on single-use plastics (Directive (EU) 2019/904 on the reduction of the impact of certain plastic products on the environment), which aims to prevent and reduce the impact of certain plastic products on the environment and promote a transition to a circular economy. Through a series of new measures, a sustained quantitative reduction in the consumption of certain single-use plastics for which there are no alternatives is required. In addition, a 90% collection target has been set for single-use plastic beverage bottles by 2029, with the incorporation of 25% recycled plastic into PET beverage bottles from 2025 and 30% into all plastic beverage bottles from 2030.

On 25 March 2021, the European Parliament adopted a non-legislative resolution that aims to reduce marine litter. Specifically, the resolution has as its goals:

- to increase collection, recycling and upcycling in the fisheries and aquaculture sector;

- to gradually phase out the use of expanded polystyrene in fishery products;

- to establish an EU action plan to clean up polluted rivers.

READ ALSO: Reuse: taking stock.

Italian regulations

Salvamare Law

On 11 May, the "Salvamare law" – or Law no. 60 of 17 May 2022 Provisions for the recovery of waste at sea and in inland waters and for the promotion of the circular economy – was enacted (OJ General Series no. 134 of 10-06-2022) The law allows fishermen and various industry associations to collect and bring ashore waste from the sea, lakes, rivers and lagoons and deliver it to designated spaces set up in Italian ports. The legislation includes the following:

- it introduces definitions of unintentionally fished waste (UFW) and voluntarily collected waste (VCW), not only during cleanup campaigns in the sea, lakes, rivers and lagoons but also through capture systems;

- unintentionally fished waste is treated the same as ship waste under the European directive: it can therefore be delivered separately, and free of charge, to the port collection facility;

- provisions are made for monitoring and control in the marine environment;

- an interministerial table will be established at MiTe (Ministry of Ecological Transition) to coordinate action to combat marine pollution, optimise fishermen's action, and monitor trends in waste recovery;

- every year, the Minister of the Environment must send a report on the implementation of the law to parliament;

- it introduces rules for the management of beached plant biomass for their reintroduction into the natural environment, including by sinking it back into the sea or transferring it to the dunal environment or other areas belonging to the same physiographic region;

- it provides for the promotion, in schools of all levels, of activities on the conservation of the environment and, in particular, the sea.

- MiTe will launch a three-year experimental programme, funded with EUR 6 million, for the recovery in rivers of floating waste, compatible with hydraulic and ecosystem protection requirements.

Some examples of national and international campaigns to clean the oceans and seas

Clean Seas: In 2017, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) launched the Clean Seas campaign. 69 member countries joined, covering 76% of the world's coastline. Clean Seas is UNEP's international campaign to reduce and prevent plastic in the seas and oceans. The campaign is joined by governments, businesses, the world of sport and private individuals who are working to promote the message of clean seas: remove plastic waste and produce as little of it as possible including by replacing single-use plastic products with equivalent goods made of biodegradable material and through innovation and ecodesign.

So far, signatories represent 76% of the world's coastlines.

4Ocean is a campaign started in the US. Equipped with nets, trucks and boats, activists systematically pick up litter along the coasts: in less than a year the association has collected about 40,000 kg of waste from the waters and coasts of the US, Caribbean and Canada. The group is made up of a core group of local employees and cleaners: volunteers, young people, workers, the elderly and even tourists who regularly board the association's five boats to clean up the sea.

World Oceans Day: World Oceans Day is celebrated on 8 June every year. The Anniversary Day of the World Conference on Environment and Development in Rio de Janeiro provides an opportunity to reflect on the benefits that the oceans provide to us and the duty incumbent on every individual and community to interact with the oceans in a sustainable manner so that current needs are met without compromising those of future generations.

Clean Up The Med is the Legambiente campaign that since 1995 has coordinated associations, schools and local institutions that dedicate one weekend in May to cleaning beaches and natural sites. Clean Up The Med transcends national borders: it covers a wide area in 21 Mediterranean countries through the activity and organisation of more than 150 players.

Fishing for litter by the Lazio Region and COREPLA: in 2021, Lazio fishing boats recovered 25,000 kg of plastic at sea. Similar initiatives have been implemented in Abruzzo, Tuscany, Marche and many other locations.

Plastic Busters: Established in 2013, Plastic Busters aims to provide a concrete opportunity for projects that contribute to a common goal: to effectively address the problem of marine litter in the Mediterranean Sea. The campaign aims to monitor, assess, mitigate and prevent marine litter to reduce its environmental, social and economic risks.

GenerAzione Mare is WWF's campaign to promote the protection of the Mediterranean sea and its great biodiversity. Actions include eliminating plastic pollution in nature by 2030.

The United Nations Ocean Conference

The second United Nations Ocean Conference was held in Lisbon from 27 June to 1 July 2022. The conference is part of the Decade of the Ocean initiatives launched by the UN to promote greater knowledge and protection of the oceans.

The goal of the event was to mobilise the international community to engage in finding sustainable solutions for the conservation, protection and responsible use of marine resources, according to Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 14 of Agenda 2030. "Save our ocean, protect our future" was the slogan chosen for this edition of the conference, during which four actions to safeguard our seas were discussed: sustainable economy, pollution, protection and innovation. Policy decisions must focus on investments in energy and food geared toward sustainable development. The ocean must become a model for managing the global commons, reducing pollution from both land and marine sources. The third goal will be to address climate change by investing in climate-resilient coastal infrastructure and protecting populations whose well-being depends on the state of the oceans. Scientific research will be the basis for finding concrete solutions in ocean protection.

Bibliografia

Littering

UNEP, 2021, Drowning in plastics, marine litter and plastic waste vital graphics, unep.org https://www.unep.org/resources/report/drowning-plastics-marine-litter-and-plastic-waste-vital-graphics

Ecomondo, 2021, Marine litter il punto della situazione, ecomondo.com/ https://www.ecomondo.com/blog/17821206/marine-litter-il-punto-della-situazione

Legambiente, 6 novembre 2020, Marine Litter un mediterraneo unito nella lotta ai rifiuti di mare, legambiente.it https://www.legambiente.it/comunicati-stampa/marine-litter-un-mediterraneo-unito-nella-lotta-ai-rifiuti-in-mare/

Microplastiche, isole e vortici, Plastica da navi

UNEP, Inside the Clean Seas campaign against microplastics, unep.org, https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/inside-clean-seas-campaign-against-microplastics

Save the Planet, 15 dicembre 2018, Isole di Plastica: ecco le sei più grandi al mondo, savetheplanet.green, https://www.savetheplanet.green/isole-di-plastica-ecco-le-sei-piu-grandi-al-mondo

Andrea Barolini, 6 giugno 2019, Isola di plastica nel mar Tirreno, l’inquietante video di Greenpeace, lifegate.it, https://www.lifegate.it/isola-di-plastica-tirreno-video-greenpeace

Nikoleta Bellou, Chiara Gambardella, Konstantinos Karantzalos, João Gama Monteiro, João Canning-Clode, Stephanie Kemna, Camilo A. Arrieta-Giron & Carsten Lemmen, 2021, Global assessment of innovative solutions to tackle marine litter, nature.com, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41893-021-00726-2

IMO, IMO Strategy to address marine plastic litter from ships - zero plastic waste discharges to sea from ships by 2025, imo.org, https://www.imo.org/en/MediaCentre/HotTopics/Pages/marinelitter-default.aspx

Normativa

Unione Europea, 2019, Direttiva (UE) 2019/904 sulla riduzione dell’incidenza di determinati prodotti di plastica sull’ambiente, eur-lex.europa.eu, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/IT/TXT/HTML/?uri=LEGISSUM:4393034&from=IT

Parlamento Italiano, 17 maggio 2022, Legge 17 maggio 2022, n. 60 Disposizioni per il recupero dei rifiuti in mare e nelle acque interne e per la promozione dell'economia circolare (legge «SalvaMare»). (22G00069) (GU Serie Generale n.134 del 10-06-2022), gazzettaufficiale.it, https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2022/06/10/22G00069/sg

Parlamento Europeo, 2021, (Comunicato stampa) Il Parlamento esorta l'UE a ridurre i rifiuti marini, europarl.europa.eu, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/it/press-room/20210322IPR00525/il-parlamento-esorta-l-ue-a-ridurre-i-rifiuti-marini

ONU, 2015, Agenda 2030 - Obiettivo 14: Conservare e utilizzare in modo durevole gli oceani, i mari e le risorse marine per uno sviluppo sostenibile, unric.org, https://unric.org/it/obiettivo-14-conservare-e-utilizzare-in-modo-durevole-gli-oceani-i-mari-e-le-risorse-marine-per-uno-sviluppo-sostenibile/

report ed articoli

UNEP, Committing to end plastic pollution, U.S. and European Commission join Clean Seas Campaign, unep.org, https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/press-release/committing-end-plastic-pollution-us-and-european-commission-join, 01 July 2022

UNEP, 21 ottobre 2022, From Pollution to Solution: a global assessment of marine litter and plastic pollution, unep.org, https://www.unep.org/resources/pollution-solution-global-assessment-marine-litter-and-plastic-pollution

UNEP, 7 luglio 2022, A new declaration to help save our oceans, unep.org, https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/new-declaration-help-save-our-oceans

UNEP, Our planet is choking on plastic (infografica interattiva), unep.org, https://www.unep.org/interactives/beat-plastic-pollution/

UNEP, Plastics, like diamonds, last forever, celebs and experts warn, unep.org, https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/plastics-diamonds-last-forever-celebs-and-experts-warn

UNEP, 27 giugno 2022, At UN Ocean Conference, new governments commit to circular economy for plastics, unep.org, https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/un-ocean-conference-new-governments-commit-circular-economy-plastics

UNEP, 1 luglio 2022, Committing to end plastic pollution, U.S. and European Commission join Clean Seas Campaign, unep.org, https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/press-release/committing-end-plastic-pollution-us-and-european-commission-join

Dalberg Advisors (per WWF), 2019, Fermiamo l’inquinamento da Plastica: come i Paesi del Mediterraneo possono salvare il proprio mare, wwf.it, https://www.wwf.it/cosa-facciamo/pubblicazioni/fermiamo-linquinamento-da-plastica/

worldrise, 2021, Inquinamento da plastica nell'oceano, worldrise.org, https://worldrise.org/ inquinamento da plastica nell'oceano https://worldrise.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Libretto_Plastica.pdf (nota: molto didattico)

Parlamento Europeo, 2021, Plastica negli oceani: i fatti, le conseguenze e le nuove norme europee. Infografica, europarl.europa.eu https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/it/headlines/society/20181005STO15110/plastica-negli-oceani-i-fatti-le-conseguenze-e-le-nuove-norme-infografica

CNR ISMAR, 2022, E' possibile coniugare il buono stato degli ecosistemi costieri con un turismo sostenibile?, ismar.cnr.it, http://www.ismar.cnr.it/eventi-e-notizie/notizie/turismo_sostenibile

Ufficio stampa Marevivo, 20 gennaio 2022, Piccoli gesti, grandi crimini – Presentati i risultati della campagna anti-littering di Marevivo, marevivo.it/ https://marevivo.it/comunicati-stampa/piccoli-gesti-grandi-crimini-presentati-i-risultati-della-campagna-anti-littering-di-marevivo/

Legambiente, 12 maggio 2022, Indagine beach litter, legambiente.it, https://www.legambiente.it/rapporti/indagine-beach-litter/

Redazione EconomiaCircolare.com, Salvamare, cosa prevede la legge che vuole liberare il Mediterraneo dalla plastica, EconomiaCircolare.com, https://economiacircolare.com/legge-salvamare-cosa-prevede-mare-plastica/

Plastic Busters MPAs, Simulazione tecniche monitoraggio marine litter, Plastic Busters MPAs – Milazzo, isprambiente.gov.it. https://www.isprambiente.gov.it/it/news/simulazione-tecniche-monitoraggio-marine-litter-plastic-busters-mpas-milazzo

Campagne e sistemi di trattamento

The Ocean Cleanup, 2022, The Ocean Cleanup (sito web ufficiale dell'organizzazione no profit) https://theoceancleanup.com/oceans/

The Ocean Cleanup, 26 gennaio 2022, Interceptor Original, theoceancleanup.com https://theoceancleanup.com/rivers/interceptor-original/

LifeGate, LifeGate PlasticLess (campagna di sensibilizzazione), lifegate.it/ https://www.lifegate.it/iniziativa/plasticless

Ogyre, (campagna di comunicazione) ogyre.com, https://ogyre.com/

Martina Grusovin, Stop alla plastica negli oceani: si parte dal Giappone, green.it, https://www.green.it/stop-plastica-negli-oceani-si-parte-dal-giappone/#:~:text=Partir%C3%A0%20dal%20Giappone%20il%20progetto,Giappone%20e%20Corea%20del%20Sud.

The Ocean Cleanup Array, theindexproject.org, https://theindexproject.org/post/the-ocean-cleanup-array-index-award-2015-winner-community-category

Plastic Busters, Origin of the plastic busters initiative, plasticbusters.unisi.it, https://plasticbusters.unisi.it/origin-of-the-plastic-busters-initiative/

Irene Esposito, La campagna di pulizia degli oceani 4Ocean: un mare più pulito, green.it/ https://www.green.it/la-campagna-pulizia-degli-oceani-4ocean-un-mare-piu-pulito/

ONU, The United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (2021-2030) at the United Nations Ocean Conference, oceandecade.org https://www.oceandecade.org/un-ocean-conference/

The sea cleaners, Plastic pollution threatens ecosystems, economies and human health, theseacleaners.org https://www.theseacleaners.org/