WASTE RECOVERY AND RECYCLING: ORGANIC WASTE

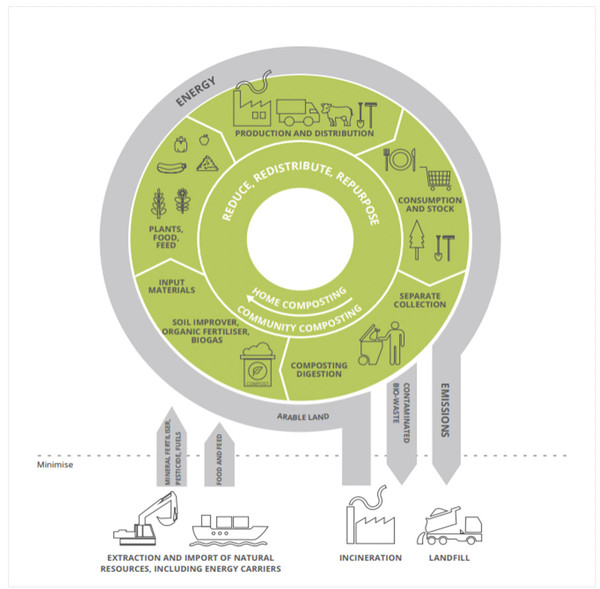

In the circular economy, organic waste, which is an important component of both the total waste generated and the recycling and recovery targets, is collected and transformed into a compost and biogas, generating numerous environmental and social benefits.

Waste as a resource

Turning waste into a resource creates a circular economy (extract raw materials, produce goods, sell them, use them, dispose of only what can no longer be used), moving away from the old linear economy model (extract raw materials, produce goods, use them, dispose of them when no longer needed). In this context, waste treatment becomes a real industrial system, also intended for the production of new, high-quality raw materials. Using secondary raw materials generates environmental benefits - no pure new raw materials are extracted - as well as social and economic benefits too, creating jobs and new business activities.

Sources:

Blog Ecomondo, Il punto sull'Economia Circolare in Europa e Italia, ecomondo.com, 2022

European Environment Agency, Waste: problem or resource?, eea.europa.eu, 2021,

The hierarchy of waste management

The waste management hierarchy originated with Directive 2008/98/EC (art. 4)1, which establishes the order of priority of actions in waste management processes to be followed in the European community:

1. Prevention (reduction),

2. preparation for reuse (reuse),

3. recycling,

4. recovery (including recovery for energy purposes),

5. disposal.

Directive 2008/98/EC puts disposal in last place, to be implemented when the previous operations, including recovery for energy purposes, are no longer possible.

Directive 2008/98/EC was amended by Directive 2018/851 which introduces the principles of the circular economy package into this sector. The new directive introduces the obligation to dispose of textile waste, hazardous waste and organic waste separately.

Disposal and recovery: what are the differences?

The concepts of disposal and recovery are defined in both European and national regulations: in European Directive 2008/98/EC and, in Italy, Legislative Decree 205/2010, which amended art.183 of Legislative Decree 152 of 2006

In general, the regulation defines recovery actions as “any operation the main result of which is to put waste to good use, replacing other materials that would otherwise be used to fulfil a particular function, or to prepare it to fulfil that function, either within the plant or in the economy in general”.

Recovery activities are divided into activities for the recovery of material and activities for the recovery of energy and they are defined in Legislative Decree 152/06, annex C:

- R1: use mainly as a fuel or other means to generate energy

- R2: regeneration/recovery of solvents

- R3: recycling/reclamation of organic substances not used as solvents (including composting and other biological transformation operations)

- R4: recycling/recovery of metals and metal compounds

- R5: recycling/recovery of other inorganic substances

- R6: regeneration of acids or bases

- R7: recovery of products used to capture pollutants

- R8: recovery of components from catalysts

- R9: regeneration or other reuses of oil

- R10: spreading on land for the benefit of agriculture

- R11: use of wastes obtained from any of the operations numbered R1 to R10

- R12: exchange of wastes to subject them to any of the operations numbered R1 to R11

- R13: storage of waste pending any of the operations numbered R1 to R12 (excluding temporary storage, prior to collection, on the site where it is produced)

Waste disposal activities are defined in annex B to part IV of Legislative Decree 152/06:

- D1: Deposit on or in the ground (e.g.: landfill)

- D2: Treatment in a terrestrial environment (e.g.: biodegradation of liquid waste or sludge in soils)

- D3: Deep injection (e.g.: injection of waste that can be pumped into wells, salt domes or natural geological faults)

- D4: Lagooning (e.g.: discharge of liquid waste or sludge into wells, ponds or lagoons, etc.)

- D5: Specially engineered landfill (e.g.: placement into separate watertight cells, covered or isolated from each other and the environment)

- D6: Dumping of solid waste into the water environment except for immersion

- D7: Immersion, including burial in the sea bed

- D8: Biological treatment not specified elsewhere in this annex which results in final compounds or mixtures which are eliminated by means of any of the processes listed in points D1 to D12

- D9: Physical-chemical treatment not specified elsewhere in this annex which results in final compounds or mixtures which are eliminated by means of any of the processes listed in points D1 to D12 (e.g.: evaporation, drying, liming, etc.)

- D10: Incineration on land

- D11: Incineration at sea

- D12: Permanent storage (e.g.: placement of containers in a mine, etc.)

- D13: Preliminary grouping pending any of the operations listed in points D1 to D12

- D14: Reconditioning pending any of the operations listed in points D1 to D13

- D15: Preliminary deposit pending any of the operations listed in points D1 to D14 (excluding temporary storage, prior to collection, on the site where it is produced)

Sources:

Stefano Maglia, Le “nuove” nozioni di recupero e smaltimento rifiuti, tuttoambiente.it,

Directive 2008/98/EC of the European Parliament and the Council, of 19 November 2008,

EU Directive 2018/851 of the European Parliament and the Council, of 30 May 2018, eur-lex.europa.eu

Legislative Decree 152/06 Environment Consolidated Law, gazzettaufficiale.it

READ ALSO: Update on the Circular Economy in Europe and Italy

The 4 Rs of recycling

Reduction, reuse, recycling and recovery are also known as the “4 Rs of waste recycling”. These actions are and are used for:

Reduction: including all those actions aimed at preventing the production of waste. Some examples are: reducing the thickness of a container, minimising packaging, choosing easily recyclable types of packaging, actions starting with the design of the goods. The category of waste reduction (or prevention) actions also includes the sale of loose products with the reuse of the same container several times.

Reuse: including all those actions in which the item or its components are reused for the same purpose for which they were created. Examples are the reuse of an older child's clothes for a younger sibling, the endless use of returnable containers, the reuse of electronic components from the disassembly of an item that cannot be repaired.

Recycling: recovery of a material in order to reuse it after it has been processed and transformed into a secondary raw material. Examples of this action are the recycling of processing waste, the traditional recycling of materials collected in separate waste collection, the use of sawdust and sawmill waste to produce pellets for use in animal bedding or wood panels.

Recovery: including all those actions the main result of which is to use waste in place of other pure materials and play a useful role. Examples of this are the regeneration or other uses of oils, the use of materials as fuel, the processing of construction and demolition waste to transform it into other materials (e.g.: as sub-bases for roads or pathways).

Separate Collection: the "fifth R"

Separate Collection is also called the fifth R, as it is the basic operation required to separate the various types of waste for the reuse, recycling and recovery of waste. Proper separate collection makes it possible to collect materials without impurities (elements with a different composition to the type of waste collected).

The basis of good separate collection is the involvement and collaboration of all those involved in the process: public administrations, the general public, businesses.

The role of the public in separate collection

Members of the general public are one of the main players in the separate waste collection chain; their actions determine both the reduction of waste at source and the quality of the sorted materials collected, and consequently their easy and inexpensive transfer to recycling procedures.

During the prevention phase and the reduction at source of waste, members of the public play an important role from the moment they choose what to buy. Preferring an item designed and produced in compliance with the principles of the circular economy (i.e.: an item with minimal packaging, made of materials and components that are easy to recycle, cheap and easy to repair in the event of breakage, durable) over a traditional product, but also generally preferring the use of reusable rather than disposable goods, means generating less waste.

Other waste prevention/reduction actions are the decision to sell or donate an item that is no longer needed instead of sending it for disposal, the decision to buy a used or reconditioned item, to share its use, to repair it instead of throwing it away, to use reusable packaging instead of disposable packaging for transporting goods.

At domestic level, attentive and precise separate collection determines the quality of the sorted urban waste collected (which depends on the amount of foreign materials in the collection) and consequently whether they are sent for recycling rather than recovery for energy purposes or disposal in landfills. The separate collection of organic waste and its subsequent composting at home, in the community or at a plant is one such action.

Benefits of separate collection and processing of organic waste

Organic waste represents over 34%2 of urban waste collected in Europe: an important component which, if properly managed, has significant potential with benefits at environmental, economic and social levels.

The chain of collection and processing of organic waste:

- is flexible: as it can be treated at both industrial and community level;

- generates environmental benefits (reduction of waste going to landfills), biogas (renewable energy), compost (which can be used both as a fertiliser in citrus farming and as an additive to repair degraded soils, helping to mitigate desertification), possibility of managing collection chains, transformation of the use of the end product at local level reducing polluting emissions from production chains;

- generates social benefits: creation of jobs in the production chain, where community composting experiences have been organised, the practice has encouraged interaction and collaboration between members of the local community.

In the European Union, separate collection of organic waste will become compulsory from the end of 2023 (Directive 2018/851), an obligation brought forward to 31 December 2022 in Italy (with the approval of Legislative Decree 11/20). However, for several years the Union has been promoting and financing projects to encourage innovation in the treatment of this waste and in the collection and processing chains.

The collection, processing and use of the end products (compost and biogas) of organic waste is a practical example of circular economy.

Figure 2) Organic waste and circular economy, source: Bio-waste in Europe report

Organic waste

Organic urban waste is the part made up of materials of organic origin in waste and consists of3:

- humid waste, i.e.: organic waste from kitchens and canteens

- biodegradable waste from the maintenance of gardens, public and private parks and urban green areas

- waste for domestic composting

- waste from markets

Sources:

Gianfranco Amendola, D.lgs. n. 116/2020 e rifiuti organici: cosa cambia e cosa resta, osservatorioagromafie.it

ISPRA, Rapporto Rifiuti Urbani 2021 (dati 2020), isprambiente.gov.it, 2021,

Prevention, recycling, reuse of organic waste

Prevention

The prevention of waste production is the most important operation in the waste hierarchy of Directive 2008/98/EC. Reducing food waste at source is therefore a priority. The measures implemented to achieve this are mainly:

- informative campaigns to raise awareness of the fight against food waste;

- the redistribution of food through the use of specific platforms;

- increasing sales of food that is about to expire or is not aesthetically perfect.

Recycling

Three organic waste treatment systems are currently popular:

- composting (treatment in the presence of oxygen),

- anaerobic digestion (in the absence of oxygen).

- Integrated aerobic/anaerobic treatment.

Other processing technologies are being developed thanks to research.

According to the ISPRA Urban Waste Report for 2021 (figures relating to 2020), the percentages of waste by type of treatment are as follows:

- Composting 48.1%

- Anaerobic digestion 5.1%

- Integrated aerobic/anaerobic treatment 46.8%

The environmental and economic benefits of the various treatments usually depend largely on local conditions, such as population density, infrastructure and climate, and on the markets for the associated products (energy and compost).

The type of treatment chosen depends on the composition of the organic waste and the characteristics of the separate waste systems. However, we can say that anaerobic digestion offers the greatest environmental benefits. The latter has the advantage of being able to generate biogas, making it a renewable energy source.

Composting can be carried out in industrial facilities or on a local scale by individuals, in their gardens or allotments, or in mini facilities shared at neighbourhood level or by small villages. This practice is called community or proximity composting and has become increasingly popular in recent years, especially on islands or in small mountain villages.

The advantage is that humid waste is transformed into compost and then reused in the place where it is produced. This avoids transport to industrial treatment plants, which would pose a problem for these locations in terms of vehicles and high costs.

The composting process takes place both in traditional compost bins and in specially designed small electro-mechanical plants.

In addition to environmental benefits, the practice of community composting produces social benefits as it encourages neighbourly relations between the people involved with the facility, which is usually self-managed by members of the community in which it is located.

Reuse

To close the chain loop, the compost and digestate need to be of good quality to ensure the production of good quality compost or digestate that can add nutrients, mineral nitrogen, phosphorous and potassium to impoverished soils, improving their capacity to retain water and nutrients, as well as to store carbon, making them more fertile.

This can only be achieved by separating organic waste at source and controlling the supply chain so that as little non-compostable material (waste such as plastics, metals, glass) as possible is collected.

The composting process

Composting is a biological process that takes place in the presence of oxygen (aerobic) during which micro organisms in the environment transform organic matter, breaking it down.

The microorganisms draw energy for their metabolic processes, triggering a series of biochemical reactions that generate water, carbon dioxide, mineral salts and stabilised organic matter rich in humus, i.e.: compost. This process occurs spontaneously in nature but in compositing facilities the process time is shortened.

Basically, in a compositing facility, we have three stages:

Mixing: the incoming material is selected and mixed to achieve the right degree of oxygenation to start the transformation activity.

Bio-oxidation: micro-organisms break down the immediately assimilable organic fraction (sugars, aminoacids, etc.) into simple compounds such as CO2, H2O and mineral salts, generating a sharp rise in heat with temperatures between 60-65°C

Ripening or humification: in this phase, the first biological processes slow down, the temperature starts to drop to 40-35°C, the organic fraction most easily attacked by microorganisms is reduced. The microorganisms present and active in the process also change during this phase. The transformation continues, leading to the formation of wet substances resulting from the oxidative polymerisation of phenolic acids and phenols, tannins and polyphenols.

During the composting process, the volume of the initial biomass is reduced by a quarter or half. The loss of volume is due to: the evaporation of water, the loss of CO2 and the reduction in the size of the material.

Sources:

Veneto Agricoltura, Progetto Compost, 2008,

Legislation and guidelines

European legislation

Directive 2008/98/EC is the reference directive on waste in Europe. It was created with the aim of providing a legal framework for the treatment of waste in the European Union. The aim was to create a management system capable of promoting environmental protection and human health, via appropriate waste management, re-use and recycling techniques, also reducing the pressure on resources and improving their use.

As already mentioned in the previous paragraphs, the directive establishes the order of priority of actions in the waste management processes to be followed in Europe (prevention, preparation for re-use, recycling, recovery (including recovery for energy purposes) and disposal.

Moreover:

- It supplies a series of definitions, such as: extended responsibility of the producer, the distinction between waste and by-products, the obligation for member states to draw up waste management plans and waste prevention programmes, conditions for the management of special waste (hazardous waste, waste oil, organic waste, radioactive waste, waste water, etc.).

- It defines a first set of recycling and recovery targets to be met.

With the introduction of the circular economy package directive 2008/98/EC was amended by directive 2018/851. The principles of the package were introduced into waste management, consolidating the importance of the waste management hierarchy in the circular economy.

The directive also:

- introduces new targets for the recycling of urban waste: by 2025, at least 55% of urban waste (by weight) must be recycled. That percentage rises to 60% by 2030 and 65% by 2035;

- introduces the obligation to separately collect textile waste, hazardous waste generated by households, and organic waste;

- proposes the creation of incentives to implement the waste hierarchy, such as landfill and incineration charges and consumption-based payment systems.

The waste regulatory framework in Europe is also completed by:

Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2019/1004 of 7 June 2019, which establishes rules for the calculation, verification and reporting of waste-related data in compliance with Directive 2008/98/EC of the European Parliament and the Council, and repeals Commission Implementing Decision C(2012) 2384 (OJ L 163, 20.6.2019, page 66);

Commission Directive (EU) 2015/1127 of 10 July 2015, which replaces annex II to Directive 2008/98/EC of the European Parliament and the Council on waste, and repeals certain Directives (OJ L 184, 11.7.2015, page 13);

Commission Decision 2000/532/EC of 3 May 2000, which replaces Decision 94/3/EC establishing a list of wastes pursuant to article 1, letter a) of Council Directive 75/442/EEC on waste and Council Decision 94/904/EC establishing a list of hazardous waste pursuant to article 1, paragraph 4 of Council Directive 91/689/EEC on hazardous waste (OJ L 226, 6.9.2000, page 3).

Organic waste management and composting are regulated by different EU legislative acts on the topics of waste recycling, circular economy and fertilisers.

According to EU directives, European states:

- must achieve separate collection of organic waste by 31 December 2023;

- may allow waste with similar biodegradable and compostable properties from packaging to be collected together with organic waste;

- They must encourage recycling, including composting and digestion, of organic waste in a way that respects a high level of environmental protection and results in a high quality output;

- encourage home composting;

- promote the use of materials resulting from the processing of organic waste.

READ ALSO: Municipal solid waste: how to reduce it by 2050

Italian legislation

Italian waste management legislation is based on Part IV of Legislative Decree no. 152/2006 Regulations on waste. This regulation has evolved over time to progressively incorporate European legislation on waste and the circular economy.

The main updates include Legislative Decree no. 116 of 3/9/2020, which implements Directive 2018/851, “amending Directive 2008/98/EC on waste and implementing Directive (EU) 2018/852 amending Directive 1994/62/EC on packaging and packaging waste”. Regulatory packages aimed at regulating different waste fractions and recovery, recycling and disposal activities complete the indications contained in the consolidated act.

As in the European context, in Italy too, organic waste, composting and compost are the subject of several legislative acts in the waste, circular economy and fertiliser sectors.

The topic of organic waste is dealt with in detail by article 182 ter of Legislative Decree 152/2006, which:

- promotes the recycling of organic waste, including composting and digestion, in a way that respects a high level of environmental protection and results in a high quality product. Its use in agriculture is only allowed for the products of facilities that comply with current fertiliser regulations;

- makes separate collection of organic waste compulsory by 31 December 2021 (however, according to ISPRA data, the separate collection of this fraction already covered over 90% of the population by the end of 2020);

- Introduces the concept of on-site composting, which includes community composting in addition to self-composting. This practice in particular is to be supported and promoted at local level, along with the use of materials obtained from recycling organic waste;

- allows the collection together with organic waste of packaging with similar biodegradability and compostability, which complies with certain criteria; for these types of packaging it also introduces the obligation of traceability by 31 December 2023, so that they can be identified and separated from conventional plastics in waste sorting plants and organic recycling plants.

With regard to the quality of the compost leaving the facilities, the reference practice is dictated by UNI/PdR 123:2021 “Test method for determining the quality of organic waste to be recovered through anaerobic digestion and composting processes” and has been defined by the Italian Standards Body, UNI, in collaboration with Consorzio Italiano Compostatori (CIC).

The new standard UNI/PdR 123:2021 specifies the analytical procedures to determine:

- the quality of organic waste resulting from separate collection to be sent for recovery through anaerobic digestion and composting;

- the number and type of disposable items used for the delivery of organic waste by users;

- the minimum number of product analyses to be carried out for a composting or industrial anaerobic digestion facility based on the amount of waste treated annually;

- the minimum number of tests to be carried out by a municipality or by an organic waste collection service operator on the basis of the resident population.

The guidelines also provide indications on the necessary instrumentation for carrying out the tests and preparing the sample, the procedures to be followed when analysing the content of impurities and the scheduling/planning of routine checks.

As regards community compositing, the regulatory references are:

- The note of the Ministry of the Environment number 004223 dated 7 March 2019 in response to questions posed by the Lombardy region;

- The Decree of the Ministry for the Environment no. 266 of 29 December 2016, Regulation on the operational criteria and simplified authorisation procedures for the community composting of organic waste pursuant to article 180, paragraph 1-octies, of Legislative Decree no. 152 of 3 April 2006, as introduced by article 38 of Law no. 221 of 28 December 2015. (17G00029) (OJ General Series no.45 of 23-02-2017) https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2017/02/23/17G00029/sg

Sources:

Legislative Decree no. 116 of 3 September 2020 Implementing (EU) Directive 2018/851 amending Directive 2008/98/EC on waste and implementing (EU) Directive 2018/852 amending Directive 1994/62/EC on packaging and packaging waste. (20G00135), gazzettaufficiale.it

Decree of the Ministry of the Environment no. 266 of 29 December 2016 Regulation on the operational criteria and simplified authorisation procedures for community composting of organic waste pursuant to Article 180, paragraph 1-octies, of Legislative Decree no. 152 of 3 April 2006, as introduced by Article 38 of Law no. 221 of 28 December 2015. (17G00029)

Stefano Maglia, Alessandra Corrù, Rifiuti organici: quali novità dopo il D.L.vo 116/2020?, tuttoambiente.it, 2020

Decree of the Ministry of the Environment no. 266 of 29 December 2016 Regulation on the operational criteria and simplified authorisation procedures for community composting of organic waste pursuant to Article 180, paragraph 1-octies, of Legislative Decree no. 152 of 3 April 2006, as introduced by Article 38 of Law no. 221 of 28 December 2015. (17G00029) (OJ General Series no.45 of 23-02-2017)

Management decisions during the COVID-19 emergency

The COVID-19 virus and the severity of its effects during the pandemic which broke out in March 2020 also had an impact on the system of separate waste collection. A number of management decisions were made by Italian lawmakers with the support of the Italian health department, the Istituto Superiore di Sanità (ISS).

These decisions were amended as knowledge of virus transmission progressed. At the beginning of the pandemic, the decision was made to interrupt separate waste collection for households where there were virus-positive individuals, by having all the household waste produced sent to undifferentiated waste. The most recent guidance dates back to 8 March 2022. The aim of the recommendations is to ensure the safety of households and the health of waste collection workers.

In the ISS recommendations, two groups of waste from households are identified:

- Waste from households where there are COVID-19 positive individuals;

- Waste from households where there are no COVID-19 positive individuals.

In the first case, where there are virus positive individuals in the household, the recommendations are to maintain separate collection but to place the waste in at least two bags, one inside the other, of the same type envisaged for the type of waste collected.

This number may be increased depending on their mechanical strength. Waste such as paper handkerchiefs, roll paper towels, masks and gloves, Covid-19 self-test swabs, etc. must be placed in a separate, sealed bag before being placed in the undifferentiated waste bag. Precautionary measures must also be taken to avoid external contamination of the bags and other waste.

If there are no COVID-19 positive individuals in the household, the separate collection instructions of the local authority apply, taking care to dispose of any paper handkerchiefs, roll paper towels, masks and gloves, and any used COVID-19 self-test swabs, with undifferentiated waste.

The guidelines also contain safety instructions for operators and companies involved in the collection and processing of waste.

During the pandemic, several studies were also carried out in relation to changes in the production of waste and the impacts of the pandemic on the environment. In general, an increase in plastic and undifferentiated waste, linked to the increased use of disposable products, masks, gloves, food containers, and protective packaging for goods, was observed at both European and national levels.

Reports produced by the European Environment Agency show the need to rethink the practices used in the management, production and consumption of disposable plastic waste in Europe.

Sources:

COVID-19 e gestione dei rifiuti: le indicazioni del Ministero dell'Ambiente, puntosicuro.it, 2020,

ISS, Covid-19: rifiuti domestici, aggiornate le indicazioni per raccolta e conferimento, iss.it, 2022,

European Environment Agency, COVID-19 and Europe’s environment: impacts of a global pandemic, eea.europa.eu, 2021,

European Environment Information and Observation Network, ETC/WMGE Report 4/2021: Impact of COVID-19 on single-use plastics and the environment in Europe, eionet.europa.eu, 2021,

European Environment Agency, Briefing COVID-19: lessons for sustainability?, eea.europa.eu, 2022,

Organic waste in Europe and Italy: data analysis

Organic waste in Europe

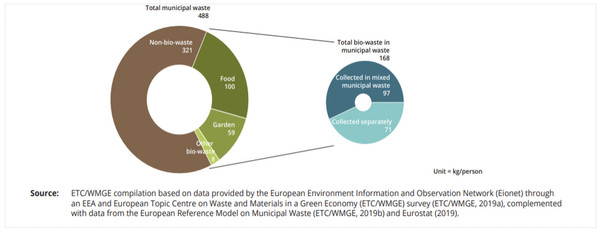

According to the figures contained in the Bio-waste in Europe report referring to 2017 (Europe, 28 Countries), organic urban waste amounts to 168 kg/resident (approximately 34% of the total urban waste produced, which is 488 kg/resident). It originates mainly from:

- food waste (100 kg/resident),

- garden - green maintenance 59 kg/resident,

- other sources (9 kg/resident).

It is collected together with mixed urban waste (97 kg/resident) or separately through its own stream (71 kg/resident).

The average amount of organic waste recycled in 2020 in Europe is 90 kg/resident.

The Bio-waste in Europe Report also points out that there are big differences between the amounts of organic waste collected in the different EU member states. A coordinated waste policy is required to overcome these differences. This must include the organic waste strategy, together with strategies for meeting the goals of the circular economy.

Figure 3) Organic waste and separate collection: quantity compared to urban waste generated and type of collection, source: Bio-waste in Europe report

The Bio-waste in Europe report

In July 2020, the European Environment Agency published a report entitled “Bio-waste in Europe — turning challenges into opportunities”, analysing the current situation and the circularity potential of this flow of waste. The report is aimed in particular at administrators, laying the foundations of knowledge in this area and supporting the implementation of management processes for this waste through the exchange of experiences and best practices.

The first part of the report highlights the importance of proper organic waste management: recycling organic waste is the key to meeting the European Union's target to recycle 65% of household waste by 2035.

The report continues with an overview of current organic waste collection and treatment systems, followed by an in-depth look at food waste, which accounts for about 60% of the total organic waste generated in Europe, with a description of the policies and main prevention actions taken to curb it.

According to the EEA, “the prevention of food waste could considerably reduce the environmental impacts of food production, processing and transport, with greater benefits than those resulting from the recycling of food waste, which continues, however, to be a necessary and important strategy”3.

According to the estimates contained in the report, much more organic waste could be recycled into fertiliser in the future than today, resulting in a high-quality product that will improve soil quality, as well as producing biogas.

In terms of treatment, composting is the most common method of organic waste management. However, anaerobic digestion resulting in the production of biogas is increasing.

The last chapter of the report analyses new alternative technologies aimed at exploiting organic waste.

Sources:

European Environment Agency, Bio-waste in Europe — turning challenges into opportunities,

Organic waste in Italy: data from the ISPRA report on urban waste

According to the data contained in the 2021 edition of the ISPRA report on urban waste referred to 2020 the organic waste collected amounts to 7,174,900 tonnes, which is equivalent to 121.1 kg/resident*year and represents 39.3% of the total waste collected using the separate collection system.

The product analysis shows the following sources of waste:

- wet or organic waste from kitchens and canteens 68.4% (4.9 million tonnes)

- biodegradable waste from the maintenance of gardens, public and private parks and urban green areas 27.1% (1.9 million tonnes)

- domestic composted waste 3.8% (275 thousand tonnes)

- waste from markets 0.7% (about 49 thousand tonnes).

Innovation for the circular economy: European projects

While the obligation to collect organic waste in Europe is scheduled to come into force in 2023, for several years now the EU has been funding research projects aimed at improving collection systems and technologies for this type of waste and, above all, at creating local supply chains that can bring environmental as well as social benefits, making cities increasingly circular. The DECISIVE project and the BIOCIRCULARCITIES project are among the most recent.

The DECISIVE project

The EU-funded DECISIVE project develops decentralised solutions for the management of organic waste. In particular, it aims to develop and demonstrate a decentralised management scheme for the innovative exploitation of household organic waste through micro-scale anaerobic digestion (AD) and solid-state fermentation (SSF) within urban and peri-urban areas.

These small plants have an annual treatment capacity of between 50 and 200 t/year. The incoming waste does not require pre-treatment. However, they require clean organic waste, collected at source with as few impurities as possible and it is necessary to identify a recovery route for the liquid fraction of the digestate before programming the micro-AD unit.

The by-products created by DECISIVE are:

- Biopesticides: stabilised solids with biopesticidal properties that can be used directly in soils either as organic soil conditioners or as biopesticides. These products can also be extracted from fermented solids and used directly as a liquid extract (liquid biopesticide, easy to apply and suitable for hydroponic crops). These substances can be used in local agriculture or in urban gardens.

- Enzymes: these can be obtained as crude or more or less purified extracts, depending on their use. They could be used locally in activities that produce cleaning products; in bio-remediation processes; in specific sectors such as the leather industry. Crude extracts can also be used to improve the AD process.

- Biosurfactants: these will be extracted and purified until a pure product is obtained. This process can be carried out with water and membranes to avoid the use of organic solvents. The products can be used in local industries for cleaning products and cosmetics.

- Bioethanol: the ethanol will be recovered by distillation and used locally as fuel or solvent in local industries.

The originality of DECISIVE lies in the transformation of organic and energy flows into a closed circuit through technological solutions for the creation of a regenerative circular economy based on organic waste management. By developing such systems, it also aims to reinforce the involvement of the general public and local employment.

It will assess the impact of these changes on waste prevention and the selection at source of other, valuable, high-quality materials in the urban waste stream. It will also focus on creating synergies with peri-urban and urban farms, using the bioproducts obtained to improve local food production.

The BIOCIRCULARCITIES project

The BIOCIRCULARCITIES project is conceived to help identify and develop comprehensive and innovative regulatory frameworks and work programmes that are well-aligned with the principles of the circular bioeconomy. It will focus on the interactions between the circular economy and the bioeconomy, using insights from multi-stakeholder participatory processes.

Innovative models for the collection and processing of organic waste in towns and cities will be developed to ensure efficient and sustainable management, also with a view to the production of bio-products with high added value.

A participatory approach will be taken, stimulating collaboration between all players in the organic waste supply chain and involving the four segments of the “quadruple helix” (industry, science, civil society and politics) with events, initiatives and living labs, to promote the “collaborative knowledge” needed to map regulatory and market potential and promote the development of the urban circular economy.

BIOCIRCULARCITIES goals:

- Identification and analysis of organic waste supply chains in urban pilot areas, with a view to pinpointing areas of potential improvement to bring them more closely in line with the principles of the circular economy.

- Identification of the best practices existing in the circular bioeconomy.

- Examination of the current national and regional political landscape and imminent legislative and political instruments on the circular bioeconomy to identify regulatory opportunities and shortcomings in the system;

- Development of a communication and dissemination plan and process for stakeholder engagement;

- Development of proactive tools and recommendations to contribute to the implementation of the circular bioeconomy. This will include proposals for political measures and innovative solutions.

- Creation of a business plan to exploit the results of the bioeconomy project.

Sources:

DECISIVE Project

BIOCIRCULARCITIES Project

Cordis, Localised circular economies for urban biowaste recycling could have global impact, cordis.europa.eu,

Notes:

1Transposed in Italy by art. 179 of Legislative Decree no. 152 of 03/04/2006 (Environmental Policy)

2 Source: Bio-waste in Europe report

3Source: Bio-waste in Europe report